Introduction

The historical development of the infrared spectrometer was described in a three-part article a few months ago. A table was presented that listed the main functional groups of an organic molecule responsible for absorption, when a photon of infrared light strikes a molecule and excites vibrations in its structure. This table can be found again here.

And we basically left things there. So in this article I am going to describe the different types of molecular vibrations in a bit more detail when we examine an infrared spectrum.

Vibrational Modes

These different types of vibrations are referred to as vibrational modes. If we take a very simple example, such as the diatomic molecule nitrogen, N2, there is only one chemical bond (actually a triple bond) between the two N atoms and therefore only one type of vibration or mode. So we would, in principle, see only one vibrational band in the IR spectrum for N2.

In fact for nitrogen, since the molecule is symmetric, an absorption band is not actually observed in the IR but one is seen in the Raman spectrum. Remember that for a molecule to be “infrared active”, there has to be a change in molecular dipole moment during the absorption. This is not the case for N2. A permanent dipole moment is not required; there only needs to be a change in dipole moment during the vibration. In the Raman spectrum, nitrogen is a “Raman-active” molecule and a band is observed, and is due to a change in the polarizability of the molecule.

These conditions, and whether a molecule is IR-active, Raman-active, or both, are called Selection Rules, which we shall meet again in a future post that will directly compare Infrared and Raman spectral band assignments.

When we go beyond the diatomic molecule, things become more complicated. A molecule can vibrate in many different ways, and each way is a vibrational mode. The actual number of available modes for a molecule can be calculated from two simple expressions:

For a molecule consisting of N atoms, if the molecule is linear, such as carbon dioxide,

O=C=O

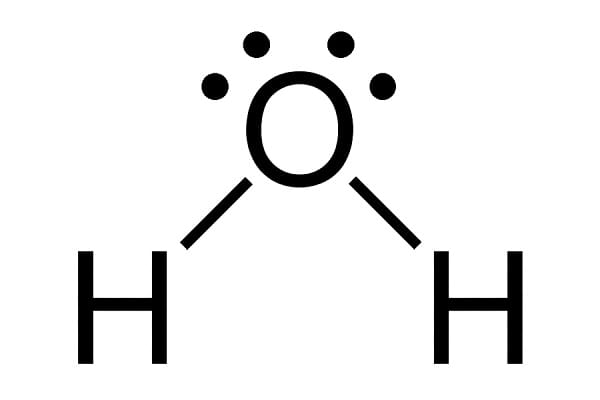

the number of modes is equal to 3N – 5. If the molecule is non-linear, such as with water,

the number of vibrational modes is equal to 3N – 6. This is also called the number of vibrational degrees of freedom for the molecule. So CO2 will have 4 vibrational degrees of freedom, while H2O has only 3.

Some common fundamental vibrations are shown in these animations for a molecule consisting of just four bonds. You can hover over each animation to see the names given to the types.

The Different Regions of an IR Spectrum

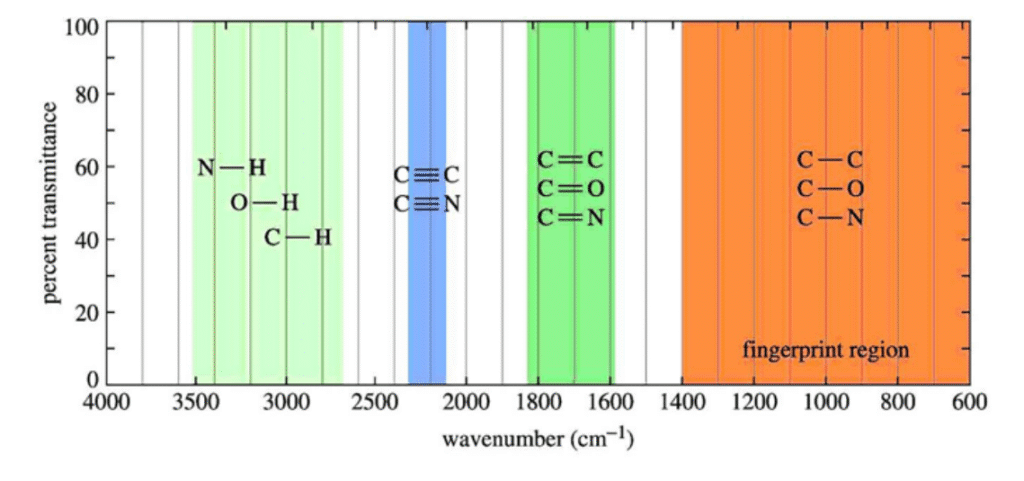

The mid-infrared range covers approximately 4000 cm-1 to 400 cm-1 (or 2.5 μm to 25 μm). This is where the majority of covalent of organic molecules normally absorb IR radiation. As a consequence, a typical IR spectrum can appear quite complex.

In order to simplify things, it is common practice among chemists and spectroscopists to divide the range into four general regions to help in analysing and characterising a sample. These regions are the X-H stretching region (where X is typically an O, N or C atom) from 4000-2500 cm–1, the triple-bond region (2500-2000 cm-1), the double-bond region (2000-1500 cm-1) and the “fingerprint” region (1500-600 cm-1). The latter is often a complex area in the spectrum exhibiting many absorption bands, frequently overlapping each other. These bands can be specific to the molecular structure of a sample. This can act as an identifying fingerprint to characterise and determine, with a good degree of confidence, the structure of an unknown sample. And if the sample’s spectrum is compared to a large library of known, standard samples, this can confirm the identity of an unknown compound with a high degree of probability.

These regions are shown in the following chart:

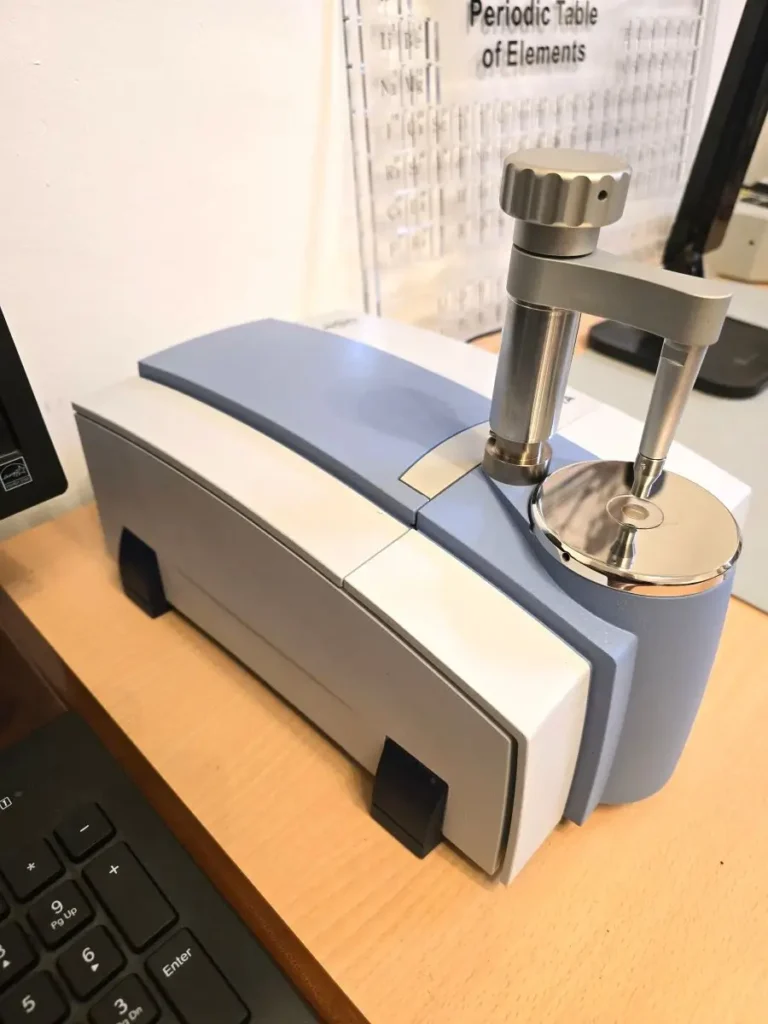

The remainder of this post gives the reader an appreciation of the general appearance and shapes of the absorption bands in the infrared spectra of some common organic compounds. All the spectra were obtained with a Bruker Alpha One FTIR spectrometer with a zinc selenide (ZnSe) ATR accessory. Units are in percent transmission (or absorbance) as a function of wavenumber in cm-1.

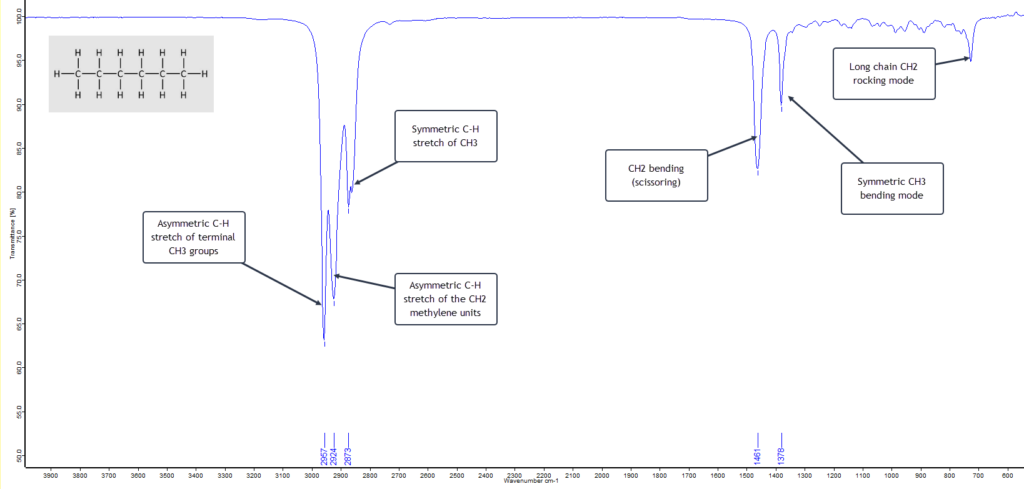

n-Hexane

n-Hexane is a six-carbon linear chained alkane. The alkanes are hydrocarbons which, as the name indicates, are compounds containing only carbon and hydrogen atoms. n-Hexane has the formula C6H14. The n in the name historically stands for “normal” hexane, as opposed to any branched chain isomers that are grouped together as iso-hexanes. The general formula for all saturated linear chain hydrocarbons is CnH2n+2 where n is the number of C atoms. Alkanes have only a few IR absorption bands and therefore each band in the spectrum can be assigned. (This is not always the case for more complex molecules with several different atoms and functional groups.) So the IR spectrum of n-hexane is relatively clean and simple as shown here with its absorption band assignments:

This is a textbook example of a saturated (i.e. no double/triple bonds) straight-chain alkane. The two strong asymmetric stretching frequencies for the two terminal methyl (CH3) groups and the inner methylene (CH2) groups at around 2960 cm-1 and 2925 cm-1 respectively, plus the lower frequency symmetric stretching mode at about 2870 cm-1 strongly suggest an alkane.

What then becomes confirmatory is the presence of the CH2 bending (scissoring) absorption band at about 1465 cm-1 and the CH3 bending mode around 1375 cm-1. Also the relatively weak, low frequency methylene rocking absorption band at about 720 cm-1 shows we are dealing with a straight-chain alkane that has multiple CH2 units.

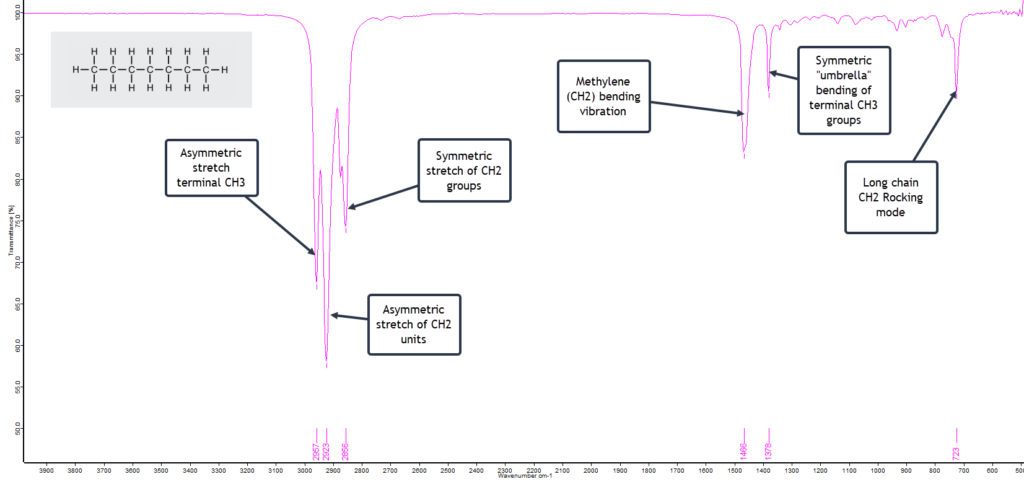

n-Heptane

The two spectra, n-hexane and n-heptane, are virtually identical, with perhaps one exception: the low frequency CH2 rocking band is slightly stronger with n-heptane. This band usually becomes slightly more intense as the chain length increases in this homologous series of alkanes.

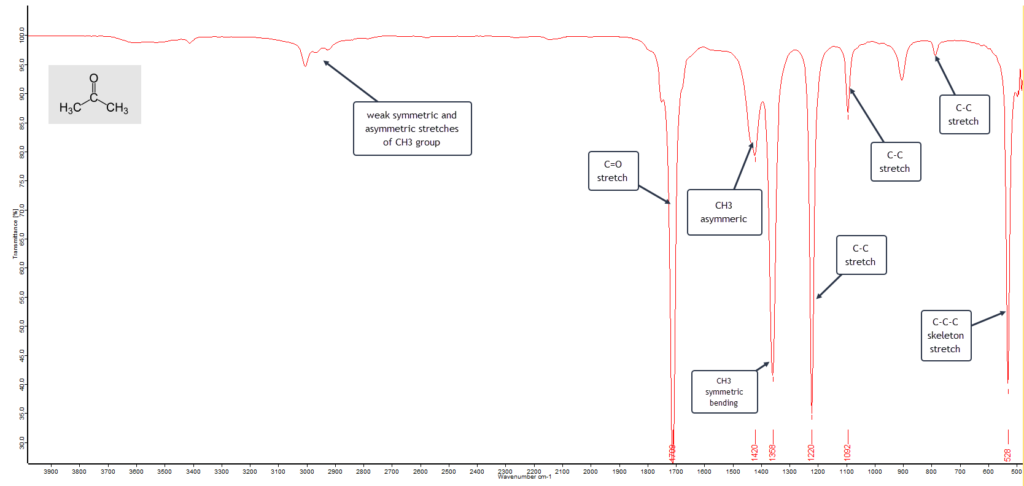

Acetone

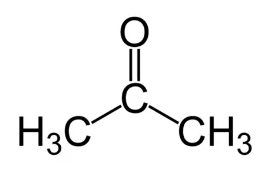

Acetone is probably the best recognised of the common organic solvents, readily available from hardware stores and supermarkets. It is miscible with water, and is used widely in industry, the laboratory and the home. Its alternative chemical names are dimethyl ketone or 2-propanone. It is the simplest of the ketone group of compounds with the structure

The general formula for the ketone family is R−(C=O)−R′, where R and R′ represent the same, or different, alkyl groups. As well as a common solvent in the home, such as nail varnish remover and paint thinners, acetone is also a common building block in organic synthesis. The IR spectrum of a pure sample of acetone is shown here:

The main vibrational absorption bands are labelled. The very strong band at 1710 cm-1 is characteristic of a keto-carbonyl group stretching frequency and essentially confirms that this is a ketone. Add to that the two strong methyl (CH3) bending absorptions around 1420 and 1360 cm-1 means that we have two “equivalent” CH3 groups attached to a third carbon atom. With these three bands alone we can be fairly confident that this is a pure sample of acetone (dimethyl ketone).

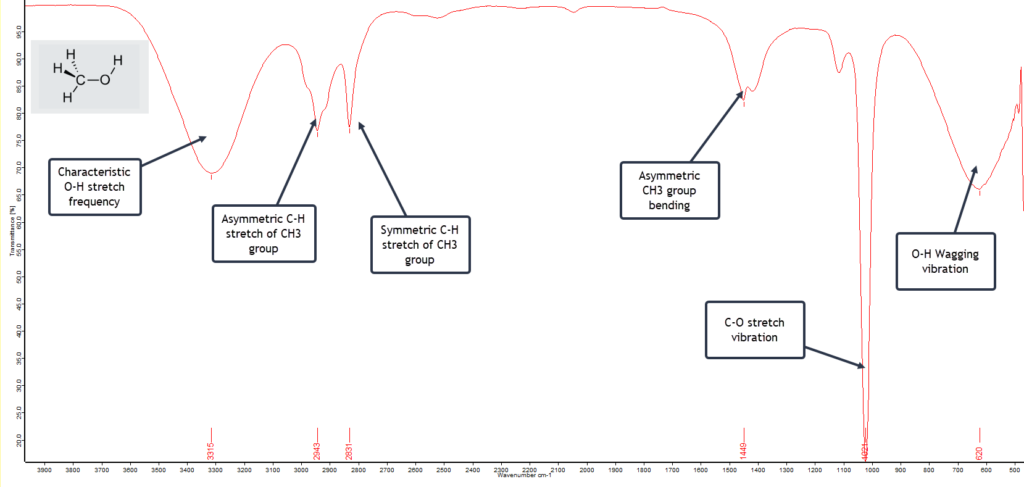

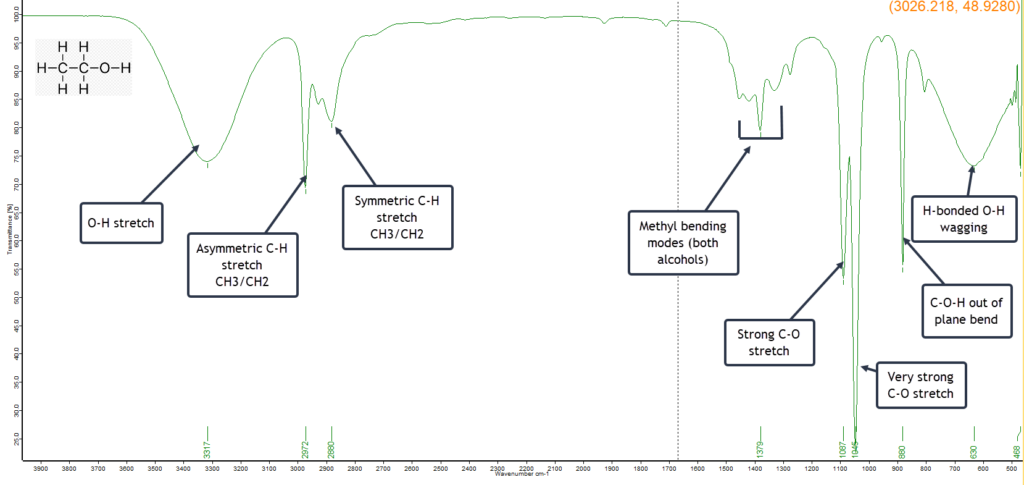

Methanol

Methanol, also called methyl alcohol, or even wood alcohol, is the simplest of the alcohols with the formula CH3OH. It is just a methyl group (CH3) attached to a hydroxyl (OH) group. The FTIR spectrum of a pure sample is shown here:

The first spectral feature to notice is the very broad vibrational band centred around 3315 cm-1 extending from 3100 to 3600 cm-1 and is due to the O-H stretching vibration but which has been broadened by extensive hydrogen bonding with adjacent molecules. Similar broadening of the O-H vibrational band occurs at the low frequency end of the spectrum at 620 cm-1. This is typical and characteristic of alcohols. The extremely strong C-O stretch vibration absorbing at 1021 cm-1 strongly indicates a primary alcohol (as opposed to a secondary or tertiary alcohol) and this particular band is stronger for methanol than for the higher alcohols such as propanol or butanol. So with a fairly high degree of confidence we can conclude that this is a spectrum of pure methanol.

Ethanol

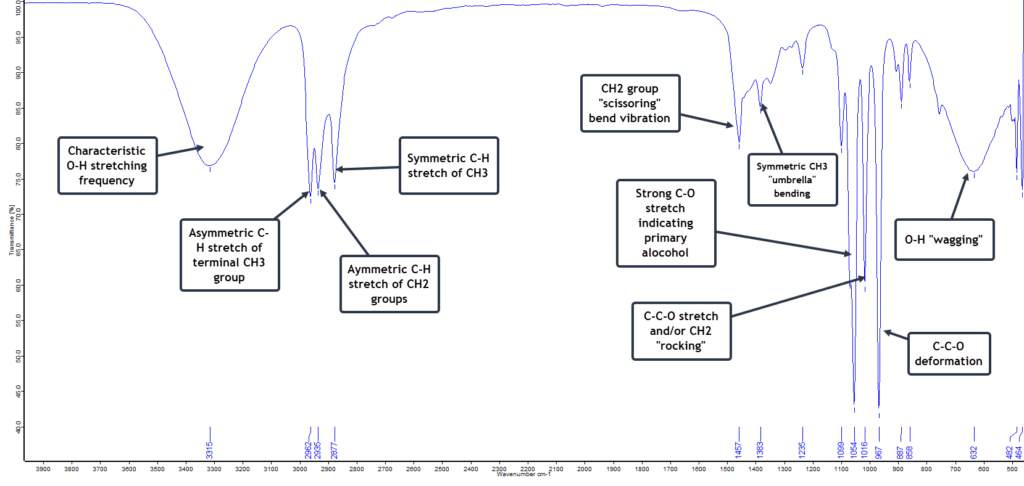

Ethanol (ethyl alcohol) is very similar to methanol, but has one extra CH2 group in its structure. So it is no surprise that the two spectra are quite similar. My sample of ethanol has been denatured with methanol to render it undrinkable. (Pure ethanol is expensive and regulated, whereas denatured ethanol is quite cheap and freely available). The amount of methanol added to denature ethanol before selling it commercially is typically 5-10% by volume.

As a result the IR spectrum (below) will exhibit characteristics of both alcohols. There are close similarities in the spectrum, such as the broad H-bonded vibrational bands, but there are also some significant differences in the fingerprint region, indicating that this is an ethanol sample that has been denatured with methanol.

The strong C-O stretch band at 1087 cm-1 is indicative of ethanol, but there is an even stronger C-O absorption at 1045 cm-1 which is a useful diagnostic showing that the sample is denatured with methanol.

1-Propanol

Also called n-propyl alcohol, simply propanol or propan-1-ol (its official IUPAC name), this is another very useful organic molecule, often employed as a solvent in several industries.

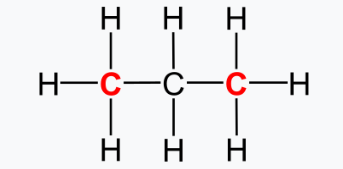

Methanol, ethanol and 1-propanol form part of an homolgous series of the primary alcohols. The primary alcohols are those where the OH group is connected to a primary carbon atom. And a primary carbon atom is an atom that is chemically bonded to only one additional carbon atom, the other bonds being to H or other atoms, as shown in this example for propane gas, where the primary carbons are shown in red.

The FTIR spectrum for 1-propanol is broadly similar to methanol and ethanol, but with some differences explained by the longer backbone.

The strong C-O stretching vibration at 1054 cm-1 indicates a primary alcohol, with the band slightly lower in frequency than with methanol.

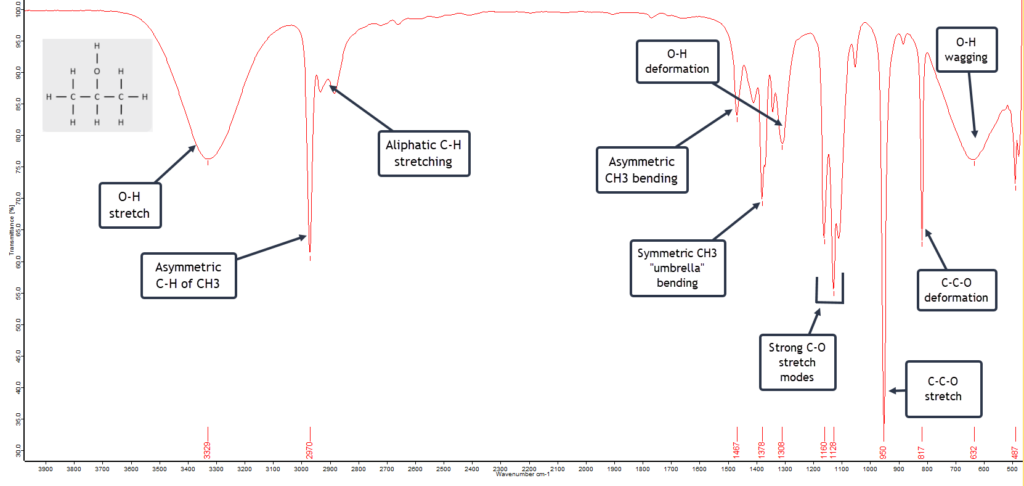

Isopropyl Alcohol

Isopropyl alcohol is also known as 2-propanol or propan-2-ol. It is also known colloquially in the lab by the acronym IPA – No, I’m not referring to the beer! 😉 It is the simplest of the secondary alcohols with the formula (CH3)2CHOH.

The expected broad hydrogen bonded O-H vibrational band at 3330 cm-1 is evident as well as the equally broad low frequency O-H “wagging” vibration centred at 630 cm-1.

A secondary alcohol such as 2-propanol has a C-O stretch vibration at higher frequency (1160 cm-1 and 1128 cm-1) relative to the primary alcohol 1-propanol (1054 cm-1) because the C-O bond is strengthened by alkyl substitution. This is often a useful diagnostic difference between the two types of alcohol.

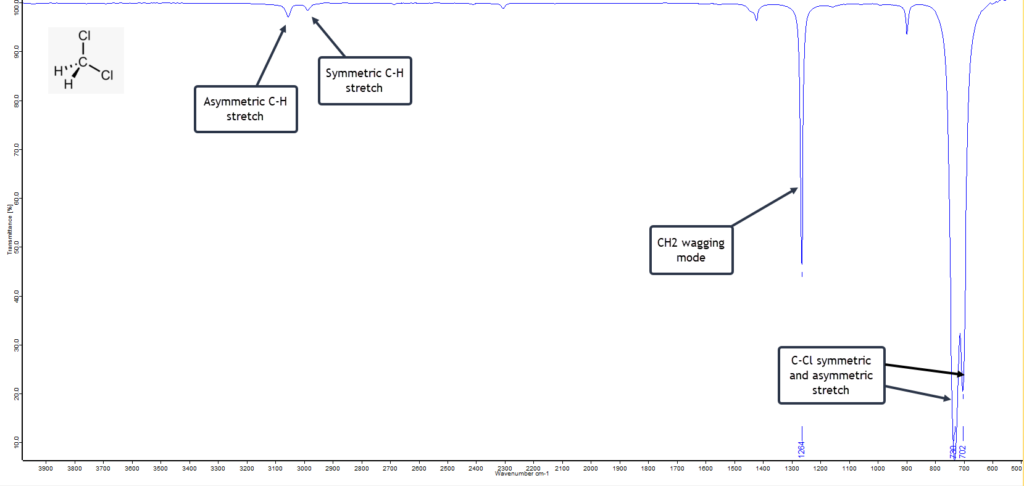

Dichloromethane

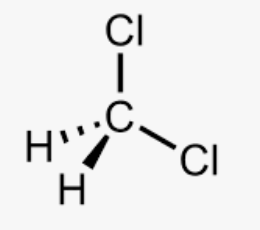

Dichloromethane, CH2Cl2, is also known as methylene chloride and is another common solvent. The liquid has a sweet, slightly cloying, odour. It is similar to chloroform in structure, but has one fewer chlorine atoms:

Dichloromethane has an uncomplicated IR spectrum. There are the usual high frequency symmetric and asymmetric C-H stretching vibrations on the left of the spectrum given below, but these are very weak. The strong and sharp band at 1264 cm-1 is the wagging mode of CH2 and is characteristic.

What confirms the molecule as CH2Cl2 are the very strong asymmetric C-Cl stretching band at 720 cm-1 and the asymmetric C-Cl stretch at 702 cm-1. The latter is diagnostic for dichloromethane.

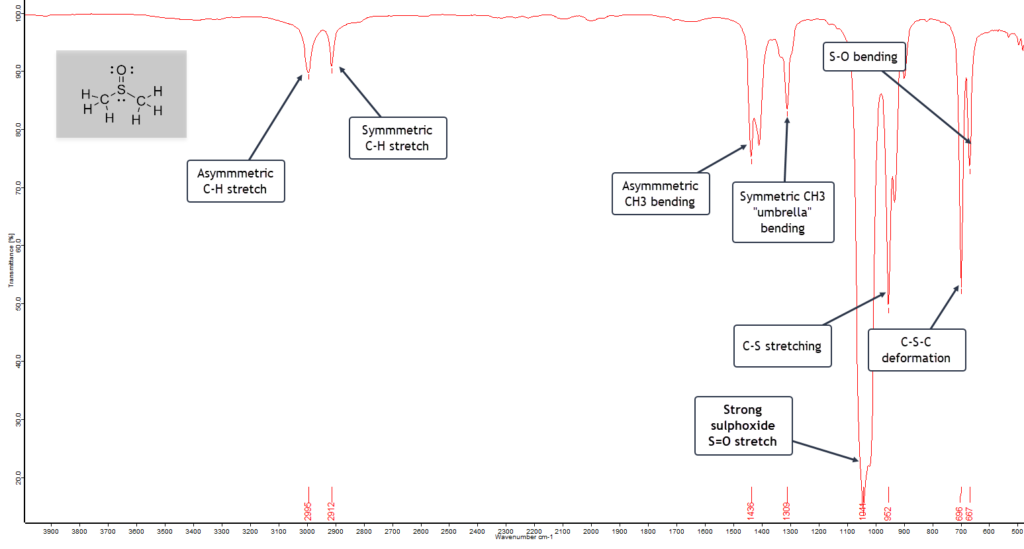

Dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO)

Finally, let’s take a look at dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO). This is another interesting solvent in organic synthesis with the formula (CH3)2S=O. It is therefore classed as an organosulphur compound. It is particularly useful in organic chemistry since it is able to dissolve both polar and non-polar compounds. Substances that do this are called polar aprotic solvents.

DMSO has a relatively high freezing (melting) point of 18.5ºC. So if stored in a cold room, a bottle of DMSO, which is a clear liquid, will have turned solid if you come to use it!

The infrared spectrum of DMSO is shown here:

The asymmetric and symmetric C-H stretching bands are weak, but the asymmetric and symmetric CH3 “umbrella” bending modes are moderately strong, since we have two methyl groups in the molecule.

The very strong S=O stretching band at 1044 cm-1 confirms we have a sulphoxide, reinforced by the C-S stretching mode at 952 cm-1. Finally, the C-S-C bending deformation mode falls in the expected range of 700 – 680 cm-1, with a low frequency S-O bending vibration 667 cm-1.

Final Words...

This is just a tiny selection from a vast array of organic compounds that have been examined by FTIR spectroscopy. Many of these are readily found online both in independent articles and also within spectral databases. A good example of the latter is SpectraBase® from Wiley, which is free once you have created an account. The database not only has FTIR spectra, but includes NMR, Raman, UV-Vis and even mass spectra of many organic compounds.

From Steve @ Steve’s Open Lab

Fascinating 🙂 Have you noticed any consistent differences in band positions or relative intensities when using ATR versus transmission for these kinds of small organic molecules?

Good question. The vibrational frequencies (band positions) will remain exactly the same. But as a general rule, the intensities are different when we compare a spectrum recorded with an ATR crystal to a spectrum recorded by transmission. A full explanation is provided in Part 3 of my article at this link using a paracetemol tablet as an example: https://stevesopenlab.org/the-infrared-spectrometer-part-3/

I’m not equipped in my lab to record direct transmission spectra of the organic solvents mentioned in this article but I expect there may well be some intensity changes. However, measuring IR spectra by ATR has become highly popular in labs over the years because of its rapidity and convenience. And in many cases, the software that commes with an IR spectrometer can often adjust band intensities automatically when required, and compensate, to enable a direct comparison with a transmission method.

Hope that helps.

Really enjoyed this. Just curious how much does the ATR crystal (ZnSe here) influence band intensities compared to other ATR materials you’ve used?